Equipping young leaders with systems literacy

By Daniel Daruty de Grandpré, Programme Assistant at The Fifth Element and Brilliant Chepkirui, Youth Climate Leader

10 September 2025

Systems literacy in action at the Youth Sustainable Development Conference 2025

In today’s rapidly evolving world, the challenges we face are complex, interconnected and constantly shifting. Traditional, linear problem-solving models often focus on treating symptoms rather than addressing root causes, making them insufficient in driving transformative and meaningful solutions.

Last month, together with the Club of Rome and the 50 Percent, The Fifth Element joined the Youth Sustainable Development Conference 2025 (YSDC), hosted by the Youth Sustainable Development Network, Africa’s premier platform for youth-driven climate action and sustainability leadership. Bringing together young changemakers to address and co-create responses to the continent’s most pressing environmental and social challenges, the conference offered participants the opportunity to work hands-on with live case studies that focused on energy and circular economy.

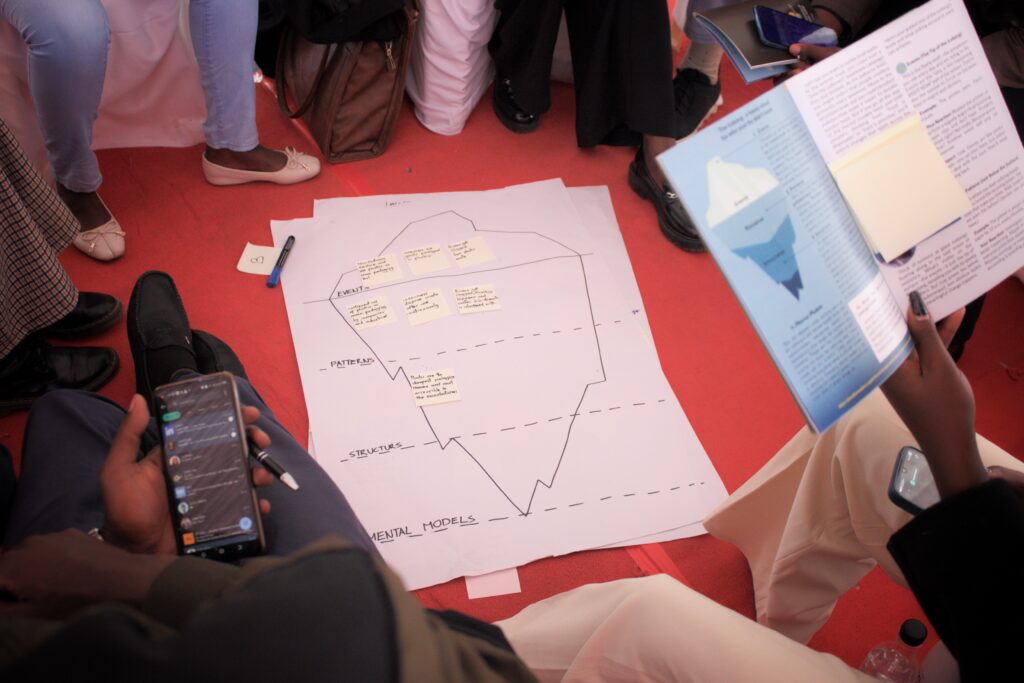

As partners of the event, our role was to embed systems literacy into this process. Through an interactive and high-energy workshop, we shared practical tools, from stakeholder and power mapping to the iceberg model, to help young changemakers move beyond surface-level fixes and toward deeper analysis of the problem landscape. This experience reaffirmed the critical need to integrate systems literacy into youth learning as a foundational knowledge area, enabling young leaders to navigate complexity and design transformative and meaningful solutions. It also highlighted a common tendency we observed throughout the case studies: the haste toward quick fixes.

The trap of quick fixes

It became clear that while the delegates were eager, naturally, many groups steered straight towards proposing solutions before fully understanding the problem landscape. Quick fixes were abundant and ingenious, no doubt, but they only seemed to treat symptoms. There was a noticeable gap in recognising and acknowledging the deeper dynamics shaping those issues.

This is not unusual. In our rush to solve the world’s most pressing issues, we often overlook the invisible forces beneath the surface: policies, power dynamics and cultural assumptions, to name a few. These “paradigms” are the elements that sustain the very problems we’re trying to address.

Introducing systems literacy tools

To help bridge this gap, our session introduced simple but powerful systems thinking tools. Nolita (Principal of Cultural Transformations at the Club of Rome) and Matias (Project lead and Co-Director at the 50 Percent) guided participants through three frameworks: stakeholder mapping, power analysis and the iceberg model.

The iceberg model was particularly well received. It shows how the events we see are only the tip of the iceberg, while patterns, structures, and underlying paradigms lie beneath. By working with these tools, groups began to see that the challenge was not only what solution to propose, but how problems themselves are structured and why solutions fail to take root if you are only treating the events in a system.

Case study highlights

Energy in rural Zambia

One group designed mini-grid systems to support agriculture. What set them apart was the way they broke down the financial architecture behind their idea.

They explored blended financing mechanisms and linked these to the policy shifts required to make the system viable. In doing so, they brought together human needs, ecological considerations, financial design, and governance into a single coherent proposal. Their work captured the essence of systems thinking by weaving multiple sectors and perspectives into one interconnected solution.

Textile waste in urban Uganda

Another group opted for challenges they felt closest to, the entrenched textile waste issue in urban Uganda for which pre-existing solutions had proven ineffectual because they mostly addressed symptoms of underlying problems. They posited a fashion upcycling project designed to curb dumping and landfill waste.

After the introduction of systems literacy tools, new knowledge was built from the iceberg model, away from reactive approaches and inclusive of mindset change mechanisms to preclude further replication of the problems. Once during discussions, participants recounted instances of defeatism brought about by the fact that every answer led to yet another layer of causality. They were challenged by the concept of a single case study being a conflation of so many elements, such that constantly asking why appeared exhausting.

The session, however, allowed them to hold multiple truths and reconcile the interconnectedness and complexity of the systems they were working on. Stakeholder mapping particularly nudged them to see the bigger picture and further analyse power dynamics. It proved a way to establish practical leverage points and build collaborations.

They opted to work the solutions back up with the most vulnerable stakeholders at the centre and posing accountability models to elements deemed concentrated with power. In systems change, solidarity becomes more than just an idea; it is a powerful tool that allows us to hold space for one another and nurture collective care.

Beyond the workshop: seeds of shift

What was most encouraging were the conversations after the session. Delegates and partners, in informal conversation, reflected on how they had been pushed to look beyond events towards the underlying paradigms. Some admitted that they wished they could have gone deeper into their case study, but spoke of the pressure of delivering a presentation the next day.

This is where systems literacy proves its worth: it encourages us to understand the problem, to pause before rushing to act, and to consider the relationships, power, and assumptions that hold problems in place.

An invitation to keep learning

Systems literacy is a crucial skill for youth leadership. To solve the complex challenges of our time, we must first understand them in their full depth and scale.

During our session, we handed out copies of the Young Person’s Guide to Systems Change. One partner reflected that it was refreshing to see systems thinking made accessible, playful, digestible, and even humorous. Rather than being trapped in high-level academic language. That accessibility matters; it means young leaders can approach complexity with curiosity, not intimidation.

The Guide is not just a resource; rather, it is an invitation to make systems literacy accessible for the leaders of the future. By equipping youth with the tools of systems thinking, we help prepare them to see and understand the world through an interconnected lens.

No comments yet