The foundational thinking behind system-level investing

By Andrea Caloisi, Researcher at Thinking Ahead Institute

20 October 2025

It may still surprise, on reflection, that social and environmental responsibility criteria seemed to arrive in the world of business and finance like a sudden awakening. The realisation dawned that, beyond the individual neoliberal unit of profit maximisation, something was owed – and owed to someone (or something) other than ourselves. The very word responsibility carries within it the idea of responding for something, of taking on the external consequences of our actions.

So, if the initial surprise is set aside for a moment, the picture becomes clearer – it was a one-way extension of humans towards others, towards nature.

This suggests a separation. And the distance from nature widened in the race of progress, to the point where we now believe ourselves ‘exempt from ecological processes’. So, I would argue that social and environmental responsibility, real-world impact and broader concepts of ethics, care and morality are all attempts at closing that gap with nature. They aim to respond for that very human ‘othering of nature’.

It’s no coincidence that these concepts can be captured by the very simple notion of ‘doing good’. After all, is there anything more other-regarding than doing good?

Let’s pause and reconsider…

This whole framework is flawed. It makes no real inroads towards securing a more sustainable future, because it is a victim of its own reductionist approach: I am I, and there are other ‘not-I’s’ out there that somehow need attention and care.

The arrival of responsibility merely shifted the ‘not-I’ boundary a little. We admitted to ourselves the co-presence of other things in our mental model of reality. The environment became something that surrounds us, something that we use, but something that most of the time remains an other. Any responsible act is viewed as altruistic (note the Latin alter, ‘other’) to benefit an external other.

Think about it – today, the mother of all reductionisms is the widespread belief that all our problems have solutions. The assumption is that, regardless of the level of uncertainty confronting us, by providing adequate resources (capital, knowledge, research, technology) and an efficient, institutionalised mechanism for allocating these resources (the market), we will eventually fix everything. Everything that is ‘not-I’.

Nonetheless, we recognise sustainability as a complex problem that we don’t know how to solve. And we come to admit that no invisible hand, no silver bullet will be able to deliver the solution. The dominant, hard ideology of reductionism – typically associated with determinism, certainty, predictability, control and rationality – is not fit for purpose. Only a more radical, transformational systems change appears necessary.

…and now let’s mend what’s broken

What we should recognise as faulty is not responsible behaviour per se, but our mindset that generates our behaviour. Bear with me as I make this a little more thought-provoking.

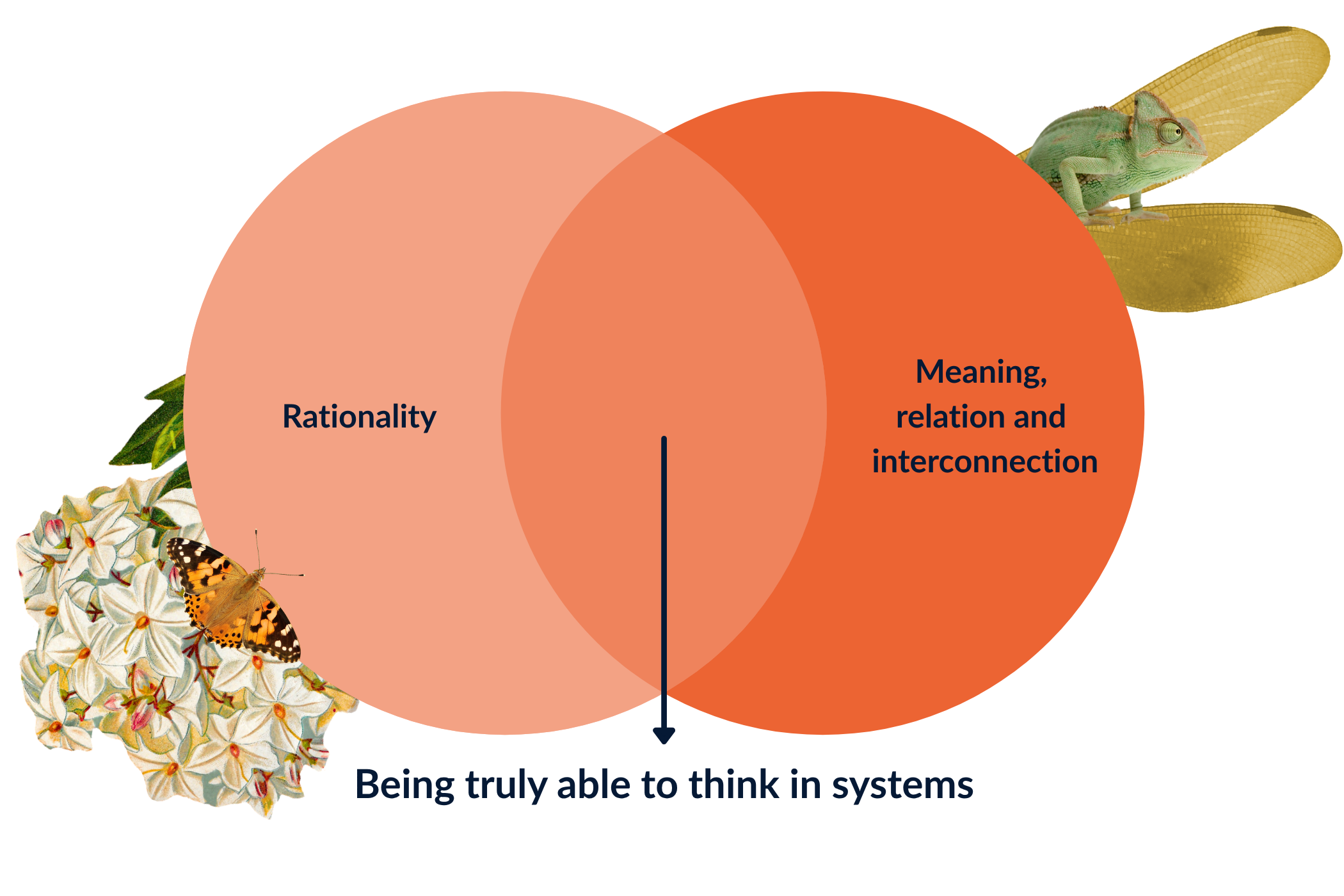

What if we were truly able to think in systems? What if rationality as the only reliable source of knowledge about the world had been complemented by a worldview grounded in meaning, relation and interconnection? It would have changed everything.

Systems thinking is not a solution; it is a mental model that allows in broader insights, mind-opening views and connectedness with nature. It bluntly reminds us that all life on Earth is interconnected. And this knowledge opens the door to purpose and meaning. Because what we erroneously perceived as ‘other’ and ‘outer’ is instead inseparable from us.

So again, what would have happened if conceiving the self as belonging to the whole had accompanied the arrival of responsible behaviour? My answer is that no ‘behavioural adjustments’ would have been needed whatsoever. We would not have needed to respond for anything at all. Because – and this is the point I wish to make – in holistic, boundary-free models of reality, ethics and responsibility come naturally.

It becomes clear now why ethics and responsibility are there, longing for a reappropriation of our lost unity with nature. A unity that, in today’s dominant worldview of control and subordination of nature, feels impossible to reclaim. Perhaps impossible to conceive, even by adding responsibility as an extra layer.

We’ve just had a glimpse at system-purpose investing

If ethics and responsibility are about ‘doing good’ – as in the classic responsible investing principles – then the holistic, relational and inclusive approach of systems thinking and purpose is about ‘being’. And while doing calls for solutions, being calls for embracing our ecosystem of interrelations and complexity.

I hope that you will agree with me that system-repurposed self-interest is the most sustainable configuration humans could ever attain.

This mode of thinking has recently – and more pragmatically – been captured by the emerging field of system-level investing. However, in my reading, the practice should not primarily be about shifting investment ‘at the level’ of the system, but to repurpose investment entirely for the sake of the whole system. For what it’s worth, this may be better described as system-purpose investing.

In other words, let’s not confuse system-level ownership with our ultimate goal. It often happens, in fact, that some investors become so large and influential that they end up owning ‘everything’ (universal ownership). But what we then want to do is invest that ownership with meaning and purpose.

The primary objective of system-purpose investing therefore is to acknowledge the inseparability of ownership and purpose at the system level.

Several important implications follow:

- Above all, we may finally be able to declare victory over the old problem of having to balance financial returns against external responsible considerations (e.g. real-world impact). The main consequence would be a redesign of this balance, likely much more in favour of impact.

- The fig leaf of fiduciary duty may fall away. Fiduciary duty could evolve from maximising portfolio returns to investing in the conditions that make returns possible. And those conditions can only be systemic.

- Systemic risk may be successfully incorporated by institutional investors, helping mobilise efforts toward the internalisation of externalities.

- ESG or responsible investing will likely disappear as unnecessary (or counterproductive).

Article originally published on www.thinkingaheadinstitute.org.