Systems thinking: the key to solving interconnected crises

By Martin Mbewe, Communications Fellow at The Club of Rome

1 December 2025

Picture Credit: iStock by Getty Images

Have you ever tried to solve a puzzle with only one piece in your hand? It is impossible to know the full picture if you only focus on one part. You might guess at the image, but without seeing how the other pieces fit together, your understanding will always be incomplete. This is the same challenge we face when looking at problems in the world. We often focus on one small part, but the real solutions only come when we step back and look at the whole puzzle. Or in our case, systems, this is what systems thinking is all about.

Why it matters

The world’s challenges do not sit neatly in boxes. Climate change cannot be solved by looking at carbon emissions alone. Global health cannot be fixed by treating one disease while ignoring poverty, food security and education. When we think in narrow ways, we risk missing the bigger picture.

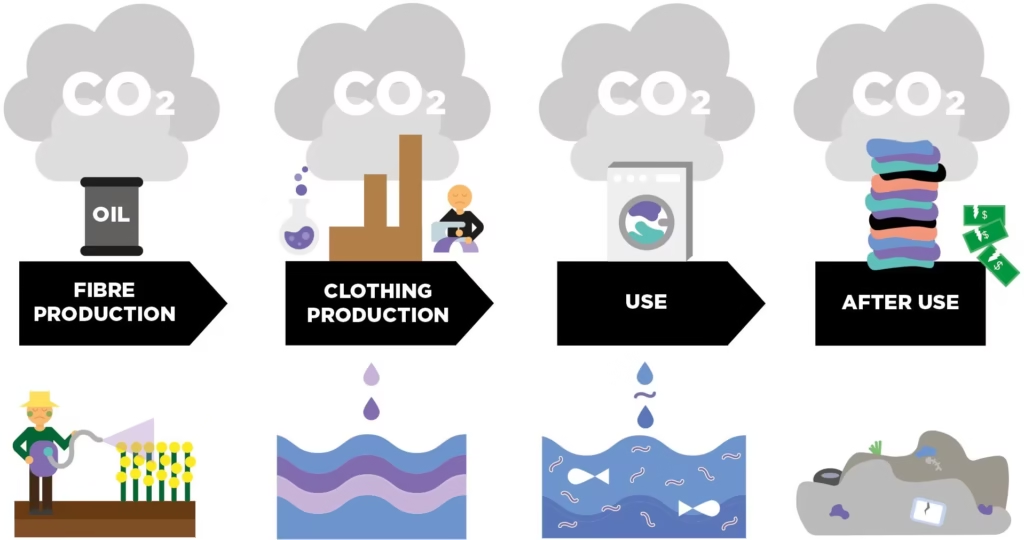

Systems thinking asks us to see how different parts connect. It pushes us to recognise that one decision in one area will ripple into another. For example, when we buy clothes, it is not only about fashion or price. It is also about the resources used to make the fabric, the labour conditions in factories, the transport that brings the items to shops and what happens when the clothes are thrown away. Each part matters because it is linked, forming a chain of impact that affects people, the planet and the economy.

Having a holistic view of a system, whether big or small, enables us to understand interdependencies, anticipate consequences and act more systemically. It helps navigate complexity and foster transformative change. This is why many members of The Club of Rome describe systems thinking as a powerful tool. We asked them to share their reflections on what this approach means to them. Their perspectives vary, yet all echoed a common message: we must move beyond silos and start seeing the bigger picture.

Voices from The Club of Rome

For Lars Mortensen, an expert in circular economy, textiles and the wellbeing economy, systems thinking starts with something tangible: the value chain. “It’s about following a product from production to consumption to disposal,” he says and then asks what happens to the waste left behind. To him, the goal is simple but radical, treat the whole system, not its isolated parts.

Katherine Trebeck, a leading advocate for a human economy, widens the lens even further. She reminds us that the planet, people and the economy are not separate spheres but one living system. “If we harm one, the effects ripple through the others,” she notes. Her message is clear: we need to step back and see how the big picture fits together.

That theme of connection also runs through Supriya Singh’s reflections. The sustainability strategist describes systems thinking as paying attention to relationships, how one organisation’s or individual’s actions shape outcomes for others. “Nothing stands alone,” she says. “Every action, no matter how small, has consequences elsewhere.”

For Songqiao Yao, founder of WildBound, the metaphor is deeply human. She likens systems thinking to Chinese medicine: when one part of the body is unwell, the entire system needs healing. “It’s not just about treating symptoms,” she explains. “It’s about restoring balance.”

Hunter Lovins, professor of sustainable business, captures this essence with a memorable line: “When you tug on anything in the universe, you find it’s connected to everything else.” Kirsten Dunlop, who leads innovation in business model transformation, agrees. “If we wish to change anything for the good,” she says, “then we need to work on those relationships.”

Economist Robert Costanza echoes that view, calling interconnectedness “the first law of ecology.” Everything is connected, he reminds us and ignoring that truth leads to fragmented solutions.

Meanwhile, John Gilmour, a social entrepreneur brings the idea down to the ground. He argues that thinking systemically doesn’t come naturally. “We’re trained to think in straight lines, cause and effect,” he says. “But complexity thinking frees me from that and helps me find multi-layered solutions that really address inequities.”

And finally, Sharan Burrow, a global voice for climate action and just transition, brings systems thinking into the political realm. For her, it’s about governments listening and responding to people’s needs, creating systems that ensure hope, inclusion and shared prosperity while tackling the climate crisis.

Across these reflections runs one powerful thread: systems thinking is not a single definition or a buzzword. It is a way of seeing the world, recognising that our challenges are not separate threads but parts of one fabric.

So, what is systems thinking?

It is a way of approaching problems, taking into account the overall system as well as its individual parts.

These different perspectives all push us to move away from siloed thinking. Siloed thinking is when an organisation, a government, or even a single person looks only at their part of the problem without considering the wider impact. For example, a company might focus only on increasing profits without thinking about how this affects workers or the environment. A government might focus on health care without considering how education or food systems shape health outcomes.

Systems thinking encourages us to ask broader questions. What factors are connected here? What ripple effects might my decision create? What is the full picture, not just the part in front of me?

The value of this approach is that it opens space for real solutions. When we look at all the moving parts, we can design responses that are more effective and sustainable. It also helps us avoid the trap of fixing one problem while making another worse.

Seeing beyond the surface

Systems thinking is not about complexity for its own sake. It is about seeing connections that are often hidden. It asks us to look beyond the surface and ask: what is really going on here?

Take the example of the fashion industry. At first glance, it is about clothes. But if we look deeper, we see it touches water use, land for growing cotton, chemical pollution, wages and safety for workers, transport emissions, consumer behaviour and landfill waste. A single shirt connects across the globe in ways we might not imagine.

Credit: Ellen MacArthur Foundation

This way of thinking also applies to social issues. If one community struggles with poor health, we cannot only send medicine. We must look at food, housing, education, sanitation and income. Health is the outcome of many connected systems.

So, systems thinking is about seeing the bigger picture. It is about looking at the whole puzzle, not just one piece. The members of The Club of Rome remind us that the world is deeply connected and that to solve its crises, we must think and act in connected ways.

No comments yet